The Rise of Xi Jinping - Part 1: The Red Princeling

In this first part we look at his early years growing up in Mao's China and how it made him who he is.

Xi Jinping leads the world’s second-largest economy and has amassed more power than any leader since Mao. Taking the helm in 2012, Xi eliminated his rivals and trashed the principle of collective leadership established by Deng Xiaoping. He is considered by many the most powerful man in the world and is steering China through some of the greatest geopolitical upheavals in modern times. What laid the foundations of Xi today can be seen in his childhood, and his years climbing the party ranks.

In this first part, we see how Xi was born into the very top echelons of Chinese society but soon found himself at the very bottom, cast aside and denounced. It was these darkest years, however, he says, that made him into the leader he is today.

Born Red

Xi Jinping was born on the 15th of June 1953 in an already privileged position. His father, Xi Zhongxun, was one of the founding members of Communist China and worked at the very centre of power alongside Mao Zedong. He would rise to be the Vice Premier and often stood in for Zhou Enlai - in essence, Zhongxun was number 3 in China’s Communist hierarchy. Being born to such a high-ranking official provided the young Jinping with luxuries not afforded to his fellow countrymen. He was admitted to the August 1st School - nicknamed Lingxui Yaolan or the Cradle of Leaders - where he was educated alongside the sons of other senior CCP members. All the students shared a unique place in Chinese society and bonded over their elite circumstances. Living together, studying together, and even holidaying together, the young boys formed a kind of brethren of Red Princelings, comparing each other’s standing with their father’s respective ranks in the party. Things weren’t always smooth sailing for Jinping. Wei Jingxun, whose younger brother was friends with Jinping, described how he was a naive little boy and was often bullied by his classmates. It seems that the playground of the August 1st School was just as cut-throat as the one their fathers occupied.

When not in school, Jinping would often visit his father in Zhongnanhai - a place with houses for the senior officials, surrounded by pleasant gardens away from the noise of Beijing’s streets, and strictly off limits for the average citizen. He would listen to his father’s stories of his early revolutionary days, such as when aged 14 he and his classmates attempted to poison their teacher, or when in 1935 owing to a feud, Zhongxun was set to be buried alive - only to be saved by Mao himself. It wasn’t just stories that Jinping’s father gave him, but also valuable lessons in being in and around the CCP. At a dinner event in 1980, the elderly Xi Zhongxun managed to toast dozens of guests all evening with his Moutai without any apparent effects. It became apparent that his glass, less containing Moutai, but water instead - a trick often used by Deng Xiaoping who rarely drank at all. He would tell his son all about revolution, how it was done, and how someday he will make his own.

Xi Jinping’s childhood meant he had a bright future where, along with his fellow princelings, he will step into his father’s shoes as the future of the CCP. Leaked US diplomatic cables showed that the US had contact with another Princeling some years later they called ‘The Professor’. He was a friend and neighbour of the Xi family. He told his US handlers that Jinping’s worldview had been formed during these years and that he had a deep sense of entitlement. He saw being the son of a CCP leader gave him the divine right to rule - a sentiment shared by many of his fellow Princelings. However, Jinping’s fortunes and that of his family would dramatically alter. The world Jinping was born into would come crashing down and plunge him into a hellish and tormented existence.

The Purge

Xi Jinping’s privileged life came to a shuddering halt in 1962, when his father was thrown from his position in the CCP and imprisoned for being a ‘traitor to Communist Ideals’. The fall of Xi Zhongxun was orchestrated by Kang Sheng who pointed to Zhongxun’s supposed support of Marshall Peng Dehuai at the 1959 Lushan Plenum, who criticised Mao’s policies. And curiously, also Zhongxun’s connection to a newly published biography of revolutionary leader Liu Zhidan who was killed in Shanxi in 1936 when the CCP was undergoing tumultuous power struggles.

Zhongxun had been a comrade of Liu and initially attempted to dissuade Li Jiantong from writing the biography. Writing biographies of key figures in CCP history was common, and writers such as Li were tasked with creating them. Despite Zhongxun’s advice, Li continued with the work and in the spring of 1960 presented Zhongxun with the manuscript. Although he criticised Li’s work and felt that he inadequately portrayed the character of Liu, Zhongxun made several suggested revisions. Kang Sheng would use this flimsy connection with the book to oust Zhongxun.

Kang Sheng had worked closely with Nikolai Yezhov - the head of Stalin’s feared NKVD - in the 1930s when Kang was living in Moscow. In fact, Kang proved instrumental in eliminating hundreds of Chinese students in Stalin’s 1934 Terror. Often suffering from psychosis and demoted by Mao several times on account of his brutality, Kang managed to spearhead the conspiracy against Xi Zhongxun by convincing Mao during a meeting that Li’s biography was somehow a veiled attempt at exonerating the disgraced Marshall Peng. ‘Using novels to carry out anti-party activities is a great invention’ said a note handed to Mao by Kang. He may have learnt the art of conspiracy and political intrigue during his time with Yezhov, but either way, he had always remained in Mao’s favour who believed his accusations against Xi.

Xi Zhongxun was sent into imprisonment at the Central Party School where he was forced to write self-criticisms, reflect on his past misdeeds, and reform himself by engaging in manual labour. The fate of Zhongxun would be shared by many thousands when following the disastrous Great Leap Forward, Mao sought to secure his leadership by triggering the Cultural Revolution in 1966. This was intended to create a cult around Mao, making it impossible to remove him. It had the desired effects but also unleashed immense terror in China - any sense of disloyalty to Mao was punished brutally.

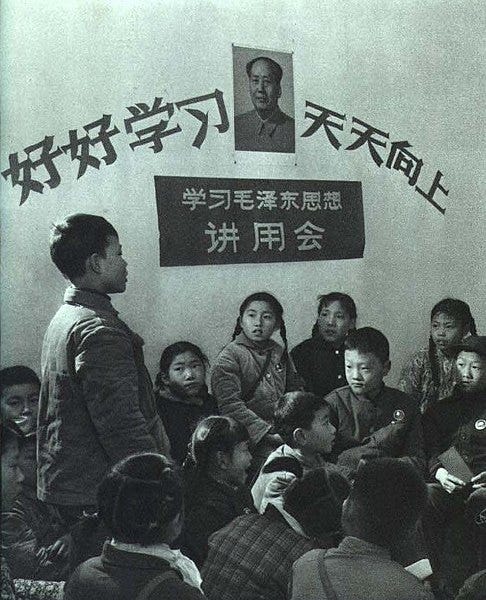

Mao’s new Revolution reached every corner of life and everyone from top to bottom. Officials, teachers, and even the police were targeted by a frenzied youth called the Red Guards, fired up by revolutionary zeal to weed out ‘Counter Revolutionaries’. The very fabric of society was torn apart. People spied on their neighbours, children on their parents, and strangers against strangers. Any sign of disloyalty or questioning was met with violence and the destruction of one’s livelihood. The chaos brought upon Chinese society caused deep scars that remain to this day.

The Cultural Revolution touched everything in China, including the exclusive August 1st School. The once tight-knit bond of the students was broken and they swiftly turned on each over based on the status of their families. Being branded a ‘Black’ person meant harassment, beatings, and humiliation, especially by the ideologically pure ‘Red’ people. Professor Feng Chongyi of the Sydney University of Technology told the ABC News podcast ‘China, If You’re Listening’ that he and his classmates were frequently forced to undergo Struggle Sessions and would be beaten for any perceived infraction, no matter how minor. Many were beaten to death - one of my aunts was beaten to death during the night he told the podcast. From August to September 1966 the Red Guards enacted extreme violence in the capital, murdering nearly 2,000 people and destroying over 4,900 historical sites. It isn’t known exactly how many were killed during the Cultural Revolution around the rest of China, but millions had their lives devastated.

These horrors were something Xi Jinping came to experience earlier than most with his father’s banishment taking place in 1962, four years prior to the official launch of the revolution. That however did not make him immune from the ravages of the Red Guards - his father’s status often made him a target of their vengeance. Occasionally, Jinping was thrown into jail whilst his mother was publicly humiliated. Crowds gathered to hurl abuse and throw objects, and families turned against each other. On one occasion when Jinping had his own Struggle Session, the crowd chanted ‘Down with Xi Jinping!’ which included his own mother Qi Xin. She was probably too terrified to deny their demands should the hyped-up mob turn on her. Jinping was not permitted to live at home with his mother but was, like his father, incarcerated in the Party School. One night he managed to escape when the guard was distracted, heading home to his mother complaining of hunger. However, she refused him and reported his escape. He was arrested and taken to juvenile detention the following day. Despite his mother’s refusal, Jinping held no ill feelings towards her, well in the knowledge that had she been caught aiding him, she would have been detained herself, taking away the only care his brother and sister had.

This unsurprisingly had an enormous effect on Xi Jinping’s mental state. The Professor spoke of this saying he had a darker side and that he wasn’t the sunniest person. This was especially so with his older sister Xi Heping, who committed suicide by hanging from a shower rail - the official report stating ‘Persecuted to Death’. He would himself come close to dying at the hands of the Red Guards. In a 2000 interview with Yang Xiaohuai, Xi Jinping described an occasion when he was captured and threatened with execution. The Red Guards challenged him with ‘How serious do you think your crimes are?’ Jinping responded with ‘you can estimate it yourselves. Is it enough to execute me?’ ‘We can execute you a hundred times!’ the guards retorted. In this interview Xi told Yang that he saw no difference between being killed once or a hundred times, so why be frightened? He believed that the Red Guards were only trying to scare him. They decided against execution and instead ordered him to read Mao’s Little Red Book all day every day. He was only 14 at the time.

Banished

Things however were set to change for the teenage Xi when he found himself onboard a train saying goodbye to his family. Rather than being sad and upset at the prospect of being taken away, he was jubilant and excited at what lay before him - much to the surprise of his family waiting on the platform. They asked how could he be laughing. His response helps highlight the desperate situation he faced every day amidst the Red Guards. Reflecting on this day, Xi Jinping said that if he stayed, he’d be crying because he could not say whether he’d live or die.

The train’s destination was Yan’an in rural Shaanxi province deep in China’s interior. Xi, along with countless others during the Cultural Revolution, was sent to work on farms to reform through hard labour. This was a fresh start for him, where he could at least escape the constant torment he received back in Beijing, and he could try to lead a relatively normal life. Upon arrival at Liangjiahe village, he was moved into a cave house which he would share with several others also sent to the countryside. He slept on a Kang bed - a basic woven mat placed on a brick structure that could be heated, very common among the Chinese peasantry. The work was intense and thoroughly shocked the 15-year-old Xi. He took to smoking to try and escape the back-breaking work as much as he could, but after 3 months he could not take it any longer and escaped back to Beijing. His time back home was brief however as he was swiftly arrested and returned to Liangjiahe.

Xi faced few other choices than to accept his circumstances and Chi Ku (吃苦) - Eat Bitterness. Life in rural China was indeed bitter. In later interviews, he described how the poor wouldn’t eat meat for months and when one day his classmate and he saw some, they simply cut a piece off and ate it raw. Albeit basic, his diet was somewhat better than the others. Due to his pedigree of being from a revolutionary family, despite the purge, he received cornflower rather than husks that the others had to make do with. Xi would work in all sorts of conditions - cutting grass in brutal winter weather, and keeping watch over the animals all night. Xi has spoken of his time in Shaanxi as a wholesome experience that built his character into what it is today. For most though, countryside life was anything but wholesome. It was a life of survival and cruelty. Starvation was a constant threat, and even cannabilism was a common occurrence. Villagers would eat anything they could to survive, from rodents to pets. Once those had gone, people would literally starve to death waiting for the rice harvest. These harsh realities were also experienced by those who accompanied Xi. One recalled how during their years in the fields, around 70 of those sent to Liangjiahe died.

Xi Jinping’s life during these years has formed a major part of his image and the propaganda surrounding him. Some of his claims are at the very least difficult to believe. One time he described how he carried a 100kg bag of wheat 3 miles across difficult mountain terrain, all without even switching shoulders! Images of Xi during these years show a man of average build, so one can reasonably suggest that this story is likely an exaggeration. He also said that he’d read all night by candlelight. Considering that the daytime work was difficult, this might be too a twisting of the truth. Accounts of others though do suggest that he did indeed read during some of his free time.

Homeward Bound

After 7 years in Liangjiahe Xi Jinping was released from his banishment and returned home in 1974. At this point, Mao had grown old and very frail, and the Cultural Revolution he triggered had died down from its ferocious apex in the late 1960s, allowing those persecuted to slowly rebuild their lives.

When Xi Jinping returned to Beijing, he had to chance to reunite with his father after many years. Initially, Xi Zhongxun did not recognise his son. Years of interrogation, torture, and isolation had taken their toll on the old revolutionary. However, when he realised who this now grown man was, he wept. Xi Jinping offered his father a cigarette. Somewhat surprised by his son’s habit, Zhongxun asked why he smoked. Jinping simply said ‘I’m depressed. We’ve also made it through tough times over these years.’ He was quiet for a moment, but Zhongxun offered his permission for Jinping to smoke in his presence.

The story of Xi Jinping’s reunion with his father was no doubt one seen thousands, if not millions, of times across China as the country began to emerge from the chaos, destruction, and violence that had rocked society for over a decade. Mao’s death in September 1976 brought an official end to the Cultural Revolution and now the country could begin to heal.

Xi Jinping returned home a changed man after his time in Shaanxi, and would soon be building his own future in the new China. A China that would open up under Deng Xiaoping’s reforms, setting the stage for Xi’s climb to the top job.

Thank you for reading Part 1 of The Rise of Xi Jinping. Part 2 will follow shortly. If you have any comments or feedback, please do get in touch!