In the first part of In China Skies, we saw how Chinese civil aviation’s difficult birth eventually led to a functioning airline industry but had its promise of a bright future interrupted by the onset of war. Nevertheless, it played a key role in maintaining Chinese resistance. Peace however would continue to elude the beleaguered carriers as immediately following Japan’s surrender, civil war once again rocked the country. Peace only returned after the face of the country had changed forever, by which point it was too late for these budding airlines.

In this part, will see how China’s airlines would be reborn under a new state with a new set of challenges, and how these laid down the foundations of what we see today.

Revolution

In 1949, the Communists under Mao Ze-dong defeated Chiang’s Nationalists and proclaimed the founding of the People’s Republic of China. After years of conflict, China’s civil aviation was in a very sorry state with only around 200 airframes in the country, of which only 17 transport aircraft remained serviceable despite the US injection of aircraft during the Second World War. This coupled with a severe scarcity of fuel, the poor state of the airfields, and that 47% of crews flying them before 1949 were American, meant that any kind of civilian air travel in the new PRC would need to be built essentially from scratch and with substantial outside help.

The two airlines that did serve China before the Communist victory, CNAC and CATC, moved their 71 aircraft to Hong Kong before they could be captured by Mao’s army. Since Autumn 1949, they did fly sporadic sorties to areas on the mainland that had yet to fall to the Communists, but the crews soon refused to return to the mainland, most joining the Nationalists fleeing to Taiwan. Their fleet became all but abandoned. However, both sides of the conflict had a great interest in acquiring this substantial fleet.

CAT (Civil Air Transport), established in 1946 by Claire L Chennault and Whiting Willauer, had become deeply involved in the Chinese Civil War and had been instrumental in evacuating some 100,000 Nationalist personnel to Taiwan. Willauer had contacts in Washington who were interested in using the stranded aircraft in Hong Kong to aid Chiang against the Communists from Taiwan and Hainan - that hadn’t yet been taken. The US up to this point had seemingly little interest in events between the Nationalists and Communists, however, they appeared to have concerns over Mao getting hold of these aircraft.

Hopes of using the aircraft for continued resistance from Chiang were put under threat when on the 9th of November, the General Managers of CNAC and CATC defected to Beijing along with 12 aircraft. It was clear that legal ownership of what remained needed to be established soon before any more were taken. Willauer discussed with Chiang the business of securing them by having his airline - CAT - purchase the fleet and take them away from Hong Kong, and more importantly the Communists. Chiang agreed that Willauer should take possession of them and with that he had a 20-strong Sikh guard surround the aircraft whilst his CAT-employed crews immobilised them by deflating the tyres. The local British administration however ordered the guards be removed lest it caused trouble with any potential Communist sympathisers in the city. For the time being, the British decided to not allow anyone to take the aircraft until proper ownership could be determined.

With the support of Willauer’s contacts in Washington, a complex corporate structure was built to prepare the company for the legal challenges that would come. CAT SA was registered in Panama with its generous tax laws and relaxed regulations. CAT Incorporated was then registered in Delaware to act as the legal nominee of the airline with the relationship with CAT SA being kept secret. The primary objective of all this was to deny the Communists the aircraft, but if they could be recovered quickly, the intention was to combine the CNAC and CATC fleets with that of CAT and operate for ‘Oregon’ from Taiwan - believed to be referring to the OSS, the precursor to the CIA.1

Negotiations between Willauer and Chiang led to CAT purchasing CNAC and CATC wholesale for $4.75m, which CAT didn’t have, but was backed by the US. Despite the expensive purchase, on the 23rd of February 1950, a Hong Kong court ruled that the aircraft belonged to the new PRC after the UK officially recognised the new government in Beijing. Even after the Governor in Hong Kong received threats from representatives of the OSS, the British felt it necessary to not offend the PRC if only to protect the city’s security and the remaining British assets in Shanghai. The American reaction to the ruling was foul and immediate, but Whitehall in London remained unmoved declaring that they would not interfere with Hong Kong justice.

2 weeks later some 1000 tonnes of spares left for the Mainland, but not before Nationalist agents bombed and damaged 7 aircraft. Hong Kong rapidly became the epicentre of a worsening tug of war between the PRC and the US. The Communists were becoming frustrated at the slow progress of handing over of the aircraft, which turned to anger when, following intense legal challenges and diplomacy, they were prevented from being handed over altogether. On the 21st of May 1951, an appeal to the Hong Kong Supreme Court upheld the previous ruling on the PRCs ownership. This was however overturned on the 28th of July the following year when, with appeals from CAT Incorp, the Privy Council in London agreed to revisit the issue and decided to award the aircraft to CAT providing that they got them out of the city by October.

Due to the aircraft being exposed to the salt air for so long, they were in no flyable condition and so had to be dismantled into crates. This work had been started previously when they were being prepared for shipping to Qingdao before the Hong Kong Police stopped the operation at the request of London. Dismantling worked for the smaller aircraft, but the larger types could not and would need to be transported whole. Remarkably, with support from President Truman, the light escort carrier USS Cape Esperance collected these larger airframes, with the Pacific Far East Lines freighter Flying Dragon carrying the smaller dismantled types. They both arrived in Long Beach, California on the 19th of October.

Under Red Skies

When Mao Zedong stood atop the gates of the Forbidden City to proclaim the founding of the People’s Republic of China, the formation of an airline was quite low on the list of priorities. And as mentioned earlier, the lack of suitable aircraft in any condition to fly, and the poor condition of China’s infrastructure would mean that any attempts to construct an airline from the ashes of the Civil War would require tremendous effort and a great deal of outside assistance. Fortunately for the Communists, the Soviet Union was on hand to provide that much-needed aid. In Spring 1950, the Civil Aviation Bureau (CAB) was established based on the Soviet’s own civil aviation management structure. Although the war had ended, the running of the country remained very much under the military, and CAB was no different - remaining so until 1954 after the Korean War fell silent.

The CAB was the administrative heart of Communist China’s early aviation industry, but it was not an airline. In the same year the CAB came to be, a fifty-fifty joint Sino-Soviet venture was launched by the name of Sovyetsko-Kitaiskoe Obschestvo Grazhdanskoi Aviatsii (SKOGA) using a fleet of Li-2s, Il-12s, and Il-14s. The Soviets provided the aircraft, spares, and pilots, whereas the Chinese side was responsible for the ground crew and facilities, co-pilots, and radio operators. SKOGA operated several routes into the USSR and Mongolia from China, and only ceased operating when the Soviets released their half of the airline, for it to be absorbed into the newly formed Civil Aviation Administration of China (CAAC).

The same year SKOGA began operations, so did a purely Chinese operation by the name of the China Civil Aviation Corporation (CCAC) flying scheduled services between Beijing and Chongqing in August 1950. Initially operating 26 aircraft of US construction which had been abandoned by their previous owners. They mainly flew sorties for the military rather than civilians, but in time as the dust settled it came on to resemble a more conventional carrier. CCAC became the Chinese People’s Aviation Corporation in July 1952, before being absorbed by the CAB itself in March 1954. Between 1951 and 1956, this operation in each of its guises restored many of the domestic air routes flown before the revolution and even launched a handful of international routes to the USSR, Burma, and North Vietnam. As each airline matured CAB operations focused mostly on the South and East, whereas SKOGA, the North and West.

In 1955 however, the PRC announced its first 5-year plan which within put a renewed impetus on the development of Civil Aviation. Among other changes, the most notable is that the CAB became the CAAC who absorbed the SKOGA and CAB operations - now all airlines in China was owned and run by the CAAC which was also the administrative body for air transport in China. This would be similar to the CAA in the UK, or the FAA in the US, running its own airline. The control of the CAAC shuffled between ministries over the years but was finally settled under the State Council by 1962. The purely administrative part of the CAAC then became the General Bureau of Civil Aviation, but CAAC remained the operator of its transport aircraft under the BGCA.

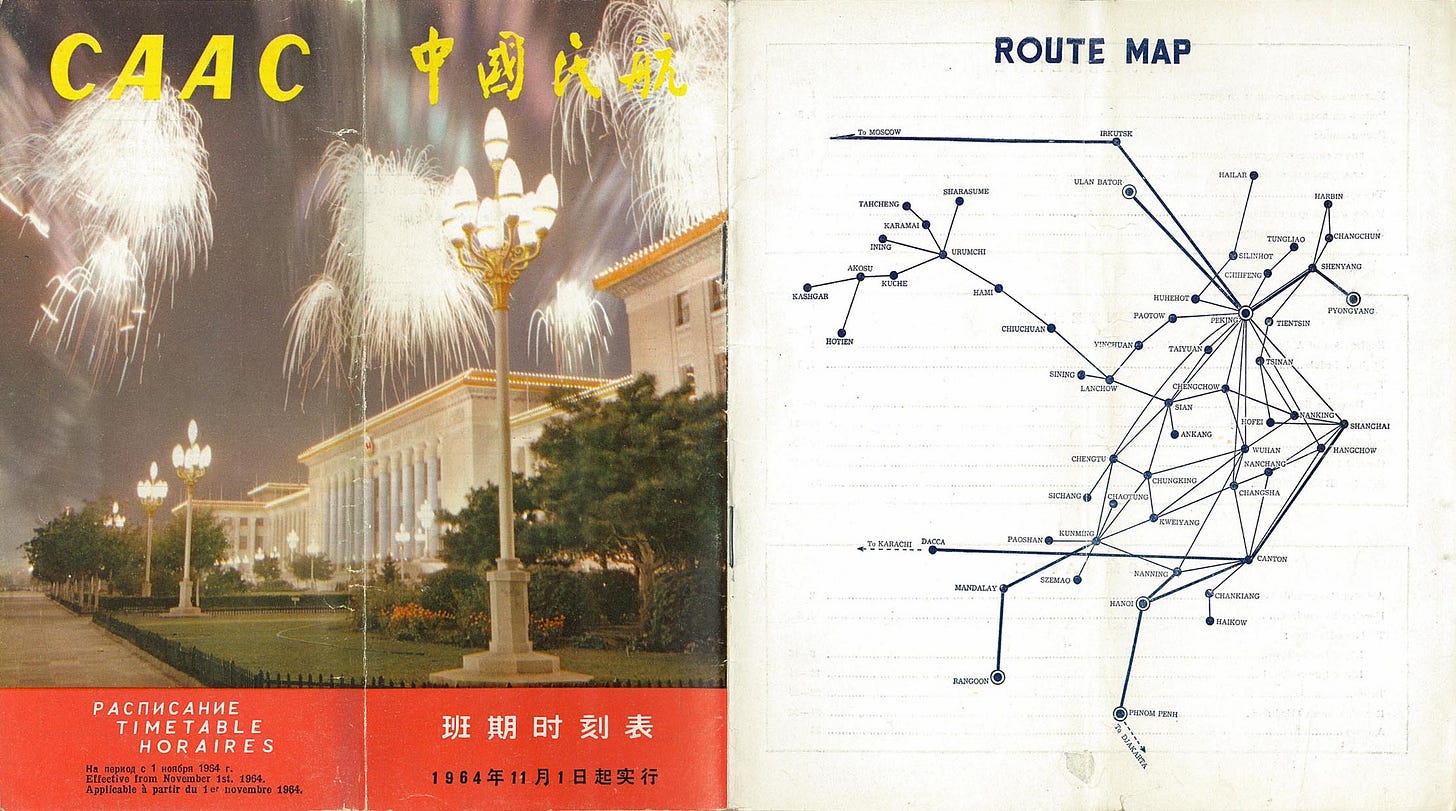

CAAC’s livery was a reserved design, with a large flag of China on its tail, blue stripping down the fuselage, which above it had the airline logo and calligraphy said to have been provided by Premier Zhou Enlai, second to Mao himself. Growth for CAAC was slow but steady with, in time, 200 - 250 aircraft serving some 80 cities with routes centred mostly from Beijing. Routes between smaller cities flew maybe once or twice a week.

Events in China had little effect on their operations until Mao launched the Cultural Revolution around 1966 to shore up his authority. This put the airline in grave danger and the State Council placed it under the direct control of military command to “protect normal flights and prepare for war”, likely born from concerns that the chaos and mayhem that crippled the rail network may befall the airline too. There was a real concern that Mao’s Red Guards who were becoming increasingly out of control would destroy airline property and potentially harass international arrivals to the country.

CAAC would not be immune however to the political upheaval the Cultural Revolution brought about. Other than ensuring that marauding students didn’t disrupt the airline’s business, the military’s other job was to be the airline’s political advisor to no doubt “weed out bad seeds and capitalists” as was one of the many slogans thrown around then. These events served to diminish CAAC’s already barebones services with flights to Central and Western China - particularly troublesome areas - being suspended unless a flight was absolutely necessary. At its peak between 1967 and 1968, air freight was especially affected and fuel shortages also became common at many airports.

For those who flew with CAAC, the Cultural Revolution made for a sharp contrast to what passengers might experience on other airlines elsewhere. The decor of the cabin called for a portrait of Mao to be placed on the forward bulkhead, and placards containing slogans and Mao’s sayings positioned on the walls. After the usual routine on takeoff, the cabin crew would then proceed to announce and sing these very quotations throughout the flight. It was common to see the more devout passengers reading Mao’s Little Red Book and discussing revolutionary thought. During the Cultural Revolution, cult-like obedience and loyalty to the party were just as important in the air as it was on the ground - or at least in one’s appearance.

Outside the main bulk of the state airline, the GBCA assigned between 200-250 smaller single-engine aircraft such as An-2s, Li-2s, and helicopters to fulfil special ad hoc services for agriculture, ariel surveying, and fire fighting. These specialised services also flew technicians and blueprints to industrial and engineering projects throughout China, as the country’s land transport infrastructure remained woefully underdeveloped.

CAAC was slow in any international growth with only a handful of routes out of China. By the late 1960s, there existed only four scheduled international services under the banner of CAAC. It seems much of the international demand for China was served by foreign carriers. PIA and Cambodia’s Royal Air Cambodge were the first in 1964 to launch flights to Shanghai and Guangzhou. Garuda Indonesia followed suit the following year until 1967 when relations between the two countries broke down. On the 20th of September 1966, Air France launched services to the same two cities - the first Western carrier to do so. Aeroflot of Russia and CAAK (now Air Koryo) of North Korea flew to Beijing on a weekly basis. Discussions did occur with Afghanistan for a CAAC service to Karachi in Pakistan flying via the Afghan capital Kabul. In March 1965, a CAAC Il-18 made a single proving flight along this route, but it never went any further than that. The lack of an international footprint for CAAC could be down to that running such an operation is deeply expensive and with the Sino-Soviet split ending Russian assistance, and the upheaval of the Cultural Revolution, it meant that CAAC just did not have the means to fly such a network, choosing instead to focus on its domestic services.

CAAC’s fleet in the 1950s and 1960s mostly contained Soviet-built types but they did purchase six British Vickers Viscount turboprops in 1961 which made up the backbone of their long-distance routes. Later they acquired Soviet-built jets, but continued an attraction to British designs, with a fleet of Hawker-Siddeley Tridents - one being the subject of General Lin Biao’s dramatic escape from China. General Lin was made aware of impending banishment as had happened to countless other officials falling out of favour with Mao. He plotted to fly on his private Trident to Hong Kong, via Guangzhou, with his family. However, his own daughter reported him to the authorities and so followed a car chase through Beijing where Lin and the loyal members of his family clambered aboard his aircraft in the dead of night. With no time to re-fuel, they rocketed out of Beijing northwards carrying merely 12.5 tonnes of fuel, hoping to reach the Soviet Union. This wasn’t to be as they crashed in Mongolia whilst attempting an emergency landing on the country’s vast grasslands in the pitch black of night, their charred remains barely recognisable.

CAAC also tried to order some Vickers VC-10s were it not for the production line of that type being dismantled sometime before. In fact, as the 1970s came around and the Cultural Revolution was dying down, CAAC made further efforts to modernise its fleet with US-built 707s. And the 1980s, as Deng Xiaoping pursued his policy of opening up the country, saw further modernisation with newer Boeing and Airbus aircraft being added to the fleet, while older Soviet designs were phased out.

Although CAAC ran a rather more spartan service than other big flag carriers around the world, passengers who did fly with them are said to have enjoyed their well-kept clean cabins, and especially appreciated the provision of hot and cold towels on the Northern and Southern routes respectively. Passenger comfort during the days post-Mao seemed to make a marked improvement as what could be ascertained by a few who wrote to the New York Times editor in March 1982. A Mr Knapp suggested that his flight with CAAC in 1982 was ‘A Great Leap Forward’ compared to his first trip with them in 1977 from Bucharest, which albeit aboard a new 707, had little more charm than a caravan passage across Asia. Another by the name of Mrs Snyder had a more rosetinted experience when her flight in June 1980 entailed boarding an un-airconditioned aircraft in 100 degrees Fahrenheit for a domestic flight. The cabin crew handed out nicely decorated fans and when one passenger’s seatbelt wouldn’t fasten, a stewardess told him not to worry and simply tied it into a bow.2

Despite CAACs renewal in the 1980s, it would soon cease to grace the skies over China. Modernisation and break-up would consign it to the history books.

The Great Break-up

Mao Zedong died in September 1976 and with him the Cultural Revolution that threatened to tear the nation apart. The China that surrounded him as he lay dying in his bed was one deeply scarred and poor. Mao’s rule had claimed up to 60 million lives and failed to create the Communist utopia he promised. Who ruled China next would determine the destiny of its people and its standing on the world stage. After an interim rule by Hua Guofeng, the exiled Deng Xiaoping would instigate immense changes that opened up the country to the world, and broke up many of the arthritic inefficient state enterprises that dogged the economy for decades. CAAC would be no different.

CAAC would not only be broken up but the entire airline industry in China would be comprehensively modernised compared to its time under Mao. This substantial task would take part over three stages. In the first ran from 1979 to 1986, where CAAC would be transitioned into a business venture by breaking it off from the airforce in 1982. Then by giving them greater financial responsibility with a scheme dubbed the ‘One-Nine’ policy, where CAAC received $1 out of $10 revenue to use how it saw fit - the airline was still state-owned and so was in no danger of bankruptcy from its measly pocket money. But this scheme allowed airline managers to develop the necessary skills in financial management and procurement that would become so crucial should the airline stand on its own feet.

Stage 2 entailed a much more radical change between 1987 and 1992. CAAC would first separate its airline business from its administrative arm making the airline a stand-alone organisation, although still owned by the state. Even though the airline would technically exist, CAAC would be broken up into 6 carriers based on the geographical area in which they were based but these new airlines would still be all owned by CAAC. Those same reforms also permitted the entry of brand new carriers which had dramatic effects. By 1993, China had 41 mostly small regional carriers that operated at a loss and were heavily subsidised by regional governments.

This overheated market led to Stage 3 which following a report from CAAC, and approved by the State Council, called for a consolidation of the industry. With that, the 6 airlines that sprouted from CAAC would be merged into only 3; Air China which operated the international routes, China Eastern, and China Southern. Each of these airlines was given further responsibility and freedom to operate independently, making their own decisions on aircraft purchases, price setting, and overseas staffing. These changes had a greatly positive effect on the industry as a whole in China. In 1980, the country’s Revenue Passenger Kilometers (RPK) ranked 33rd in the world, but by 1998 it rose to 6th.3

Today, China is one of the world’s largest air travel markets, where a broad range of airlines grace the skies over the most populous country, from international big-ticket names such as Hainan airlines to low-cost carriers like 9 Air to small regional names such as Joy Air. The pandemic aside, China has never had it so good.

Made in China

China not only flew aircraft but also has a history of building them. Early attempts at an indigenously designed airliner proved unsuccessful. In 1958, the twin piston-engined Beijing 1 was launched with seating for 8 - 10 passengers. Only one was built, however, with the prototype supposedly seeing service with CAAC. For a long time, Chinese aircraft manufacturing mainly focused on military types, but any kind of production was constrained by inefficiencies and duplication.

In the 1970s another try was made with the Shanghai Y-10. This aircraft was a four-engined jet airliner that bore a remarkable resemblance to the Boeing 707, although about the size of the more compact 720. It is speculated that a crashed Pakistani Airlines 707 that came down in Xinjiang in 1970 was taken away and reverse engineered - something those working on the project denied. Powered by spare Pratt & Whitney JT3Ds from CAACs modest fleet of 707s, the number two prototype flew on the 28th of September 1980. It would seem that the old Soviet habit of large flight crews had continued with the Y-10 which had a crew of five; The Captain, First Officer, Flight Engineer, Navigator, and Radio Operator. The project initiator was Wang Hongwen, who by then was a member of the infamous pro-Maoist Gang of Four and so other CCP officials, fearing any association with the group, stayed well clear of the Y-10 project. Also, by its maiden flight, it was already a 30-year-old design. Subsequently, only 3 airframes were ever built of the type. A deal signed in 1992 between the China Aero-Technology Import and Export Corporation and McDonnel Douglas for the production of MD-80s and MD-90s in China put an end to the Y-10 in 1985.

China hoped to become self-sufficient in civil aircraft but never achieved it. Better luck was found though with the Xian MA60 twin turboprop in the 2000s. Based on the 1970s-produced Y-7 which was a Chinese-built version of the Antonov An-24, the MA60 has seen over 100 airframes produced, operating primarily in South America and Africa.

More recently, the Commercial Aircraft Corporation of China (COMAC) has embarked on the ambitious project of competing with Airbus and Boeing in the single-aisle market. With the first delivery of its C919 planned this year, the project has been shrouded in delays and controversy around economic espionage. Worsening relations between China and the West will mean it unlikely the type will see service in our local skies, and equally unlikely to take on the dominance of Airbus and Boeing. But the C919 promises to take the Chinese civil aviation industry to new heights.

The last 100 years for China have seen remarkable events and changing fortunes. Who knows what the future will hold, but could the next 100 years be as dramatic as the last? Today we are witnessing again a major shift in the story of China, one which will be no doubt the story of its aviation industry too.

I hope you enjoyed reading In China Skies, Part 2: 1949 - Today. More content about China and its history will come soon, so subscribe and keep an eye out in your inbox! Until then, 再见!